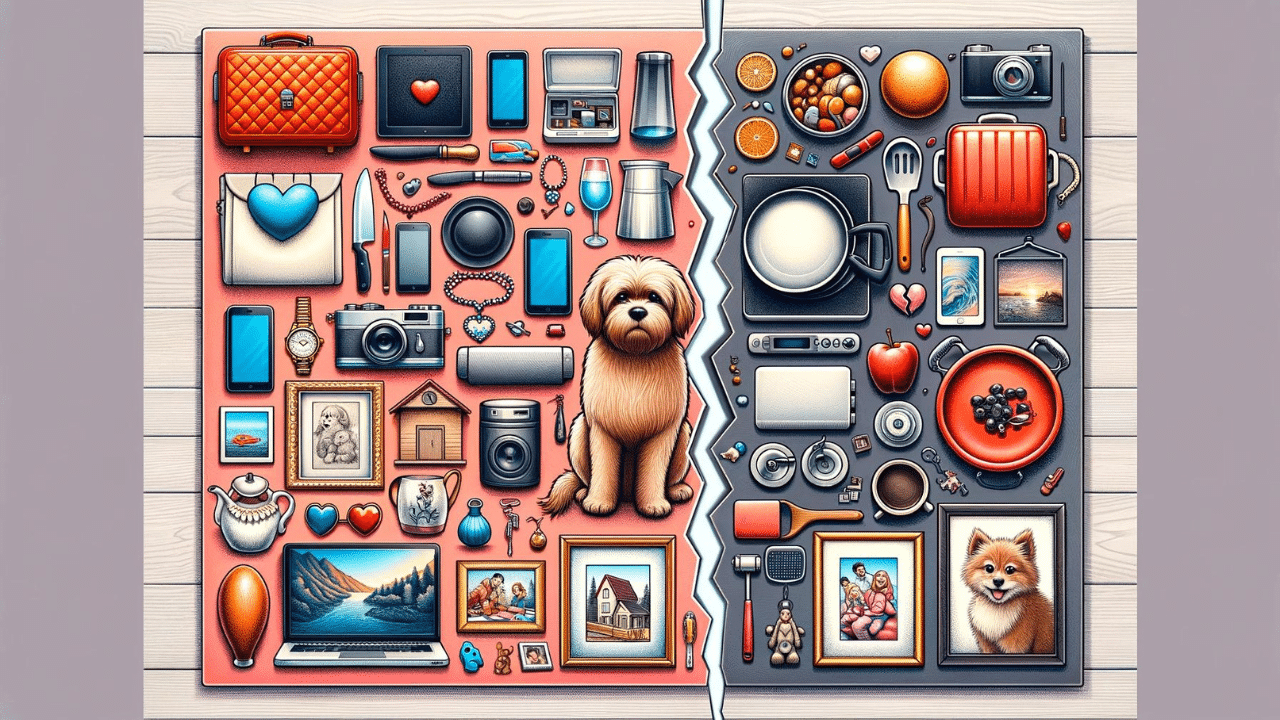

Personal property encompasses various personal items individuals own, including jewelry, electronics, and household goods. These items accumulate over the years, and during a divorce, the question of how to divide them arises. This article explores the nuances of dividing personal property in divorce cases and the considerations involved.

Definition of Personal Property

We use personal property to describe personal items someone owns. This includes items such as jewelry, clothing, handbags, electronics, cookware, photo frames, laptops, cell phones, artwork, and photographs. A residence typically contains numerous personal property items, and couples and families accumulate quite a bit over the years.

Personal property may be premarital (purchased before marriage), marital (acquired during marriage), or non-marital (such as family heirlooms).

People in the Chicago area going through a divorce are generally curious about how to divide personal property their case. But the fact of the matter is that in regular divorce situations, the courts and attorneys are “hands off” when it comes to the division of personal property, absent limited exceptions.

Valuation of Personal Property

Personal property generally holds value equal to its fair market value. If you were to sell a used picture frame to another person, what would they pay for it? Often, people donate or give away these items due to their nominal value. What about a used television set or a used laptop? For example, the resale value is typically small for a used television set or laptop.

Given the nominal value of most personal property, involving attorneys in its division often makes little sense, unless the items are exceptionally valuable, such as jewelry or heirlooms. This includes pets, which, despite being beloved by many, are often considered “personal property” in divorce cases, with some exceptions and additional rules.

Division Methods in Court

So, how do courts divide these items if the parties dispute property division? Usually, the court sets the rules for this. Some judges might instruct the parties to have an estate sale, sell everything, and split the proceeds. Other judges will tell the parties to “flip a coin” for who starts first and then take turns selecting which items of personal property they wish to keep, switching off until everything is divided.

Judges have discretion on how to divide these items. But, typically do not spend the parties’ time and money overseeing who takes the fancy china dishes and who receives the bedroom sets.

Download Our Guide to Property Division in Divorce to help you navigate these sensitive challenges

Mediation and Arbitration Options

If parties need additional assistance beyond what the Court can provide, mediation is always an option. However, the parties then likely pay a private mediator. If attorneys do not participate in the mediation, this might save money since they pay one mediator instead of two attorneys.

But, if the attorneys mediation is attorney-assisted, where counsel is representing both parties, the parties then pay the cost of the private mediator and their attorneys. Arbitration, a binding determination made by a third-party neutral (usually a mediator), is also an option, but there is usually no option for an appeal if the parties dislike the outcome.

Negotiating these items among attorneys or having a settlement conference to go through the disputed items is also an option. Ultimately, if the parties argue about coffee mugs in a conference room, they are wasting time and money – and – spoiler alert – it isn’t really about the coffee mugs.

Pets as Personal Property

What about the pets? In Illinois, companion animals are considered personal property. They are dealt with under the same section of the Illinois Marriage and Dissolution of Marriage Act which describes disposition of personal property.

However, the Court must consider what is in the best interests of the companion animals when determining who will receive them. Sometimes, the court sets visitation schedules between the parties for the companion animals. Sometimes, the parties agree on visitation schedules for the companion animals.

Before the courts received guidance of considering the animals best interests when determining who to award them to, the court often would tell folks fighting over their car or dog that they needed to sell the animal if they couldn’t agree on who would receive them.

The parties did receive that approach well. Now, with the best interests consideration, parties can “share” companion animals in a final order. However, service animals are not considered “companion animals” for purposes of awarding the animal to someone.

Importance of Documentation

So, what else should one consider regarding personal property?

Documentation. If you have items which are worth a lot of money it is likely they have been insured and appraised. Documentation like this is helpful for assessing a value for the property if it is marital.

If you receive something worth $5,000, it is likely your spouse will also receive an item or items worth $5,000 when dividing your estate (if it is a 50/50 division). These documents indicate how long you have owned this personal property, depending on the date.

If you inherit personal property, keep the documentation showing how you obtained it and that it was a non-marital inheritance, to prove that the court should award it to you.

Taking photographs of items you had prior to the marriage could be helpful. If you have or are considering a premarital agreement, attach photographs of the items you claim as non-marital. Include these photos in your agreement to prevent disputes about ownership or purchase dates.

Keep receipts and other documents for items which are special to you. It is best to start planning for the possibility of divorce before marriage to ensure you have a good record of your personal property and protect yourself in the future. You may also find value in this article about Common Mistakes in High Asset Divorce.

Conclusion

Proper documentation and a clear understanding of personal property values can streamline its division during a divorce. Being prepared and informed ensures a fair distribution of assets, whether through court rulings, mediation, or arbitration. For more personalized guidance, consult a specialized attorney.

If you need assistance with dividing personal property in your divorce, contact Anderson Boback & Marshall today. Our experienced attorneys can provide the guidance and support you need. Visit our website or call our office to schedule a consultation.